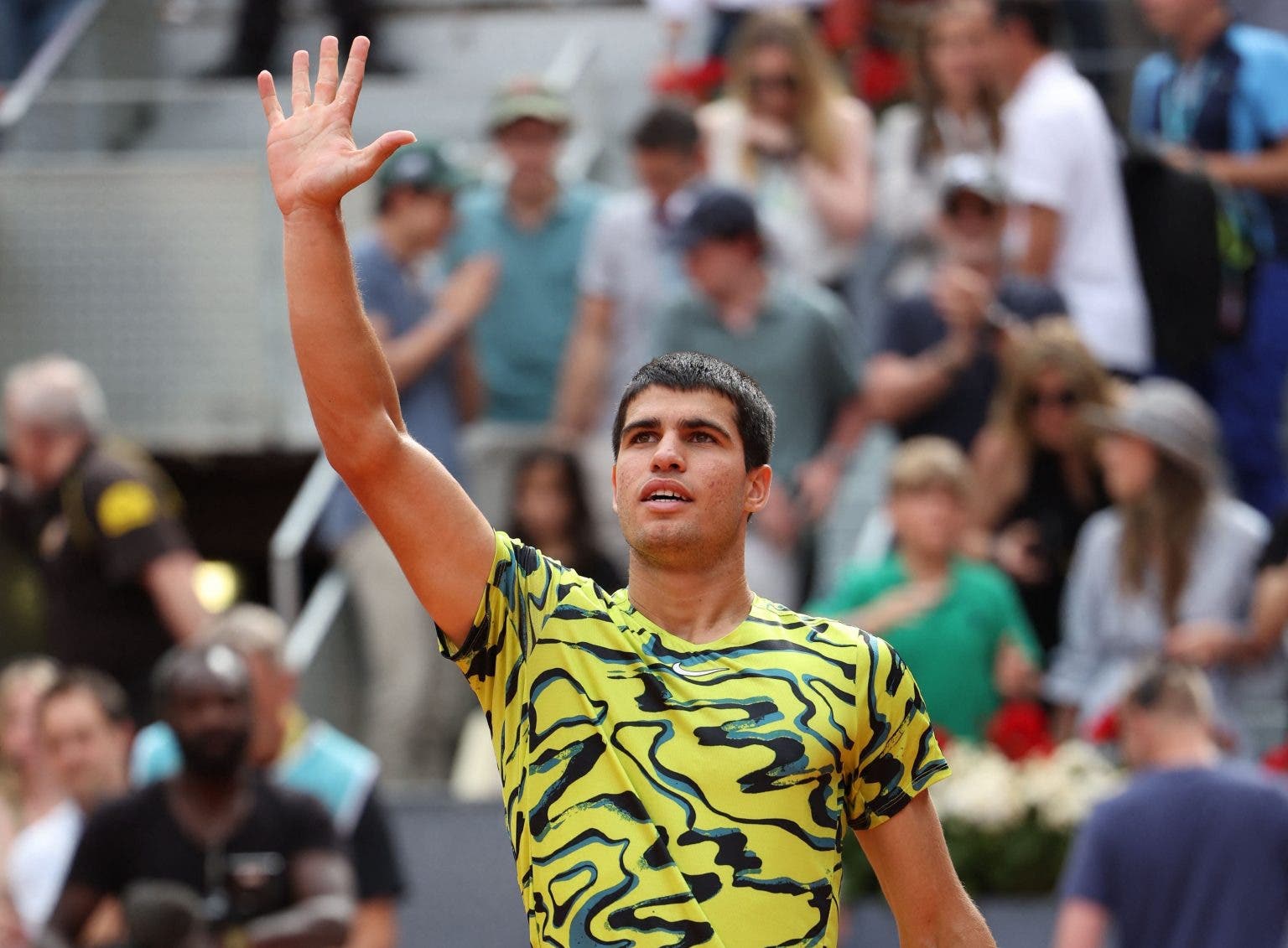

The No. 1 is about to step out on court in his new role as the favourite for the title. We take a look at some possible hurdles on his way

In the aftermath of Barcellona and Madrid, a 11 match winning streak on clay with 4 sets lost along his way, a halo of invincibility appeared to be floating around Carlos Alcaraz. He had just sailed back from his expedition across the Americas carrying a rich treasure on his galleon: two titles, Indian Wells and Buenos Aires, a final in Rio, lost to Norrie, but played in imperfect physical conditions, and a semifinal in Miami, where he lost to Sinner, the player who could really be his nemesis.

Even more impressive than the stats was the way he had soared through his matches with joyful exuberance, inebriating with a stinging variety of shots. Delight for viewers, hell for his opponents.

Carlos appeared poised for a season like Roger Federer in 2004. The Swiss great, one year after securing his first Major at Wimbledon, had one of best seasons: a win loss record of 74-6, 3 majors and 3 Masters 1000. No loss to top 10 players.

Then came the Alcaraz’s defeat to Fabian Marozsan, ranked No.135, in the second round in Rome. A mediatic earthquake, one of the greatest upsets in recent years. But has Carlos really returned to human dimension, which notoriously wavers between wins and losses?

Of course not. He is still the player who in 2023 has won most matches on clay: 20. Above all his win-loss percentage is staggering: 90.91%. He’s followed by Medvedev (83.3%) Rune (81.3) and Rublev (80%).

Therefore the loss to Marozsan must simply be framed within an overall analysis of Carlos Alcaraz’s rare stumbles.

Most players, however domineering, have had an Achilles heel, which they have mitigated throughout their career. Federer’s topspin backhand, Djokovic’s serve for instance were not initially as effective as they were to become.

Even the pickiest critics will find it hard to detect a flaw in Alcaraz’s technical endowment. And against a player who can execute any shot, from any inch of the court, who can alternate power and finesse, hammer and caress from the baseline with unaltered gesture, who can serve cannonballs and kicks, who can serve and volley and even serve and dropshot, who can retrieve the unretrievable, not only will any gameplan get unsettled, and sooner or later fall apart, but planning a strategy for the match can seem a pointless task. Shrewd planning envisages a plan B, should A not work. But against Alcaraz further spelling may be required: plan A, plan B, then a plan C, still a D, and on and on, striving to find an escapeway from defeat.

Who are the players who can seriously pose a threat? Which is the gameplay Alcaraz has shown to suffer so far, in his young career?

His nemesis is Sinner so far. After losing to the red-haired Italian in Umag, 31 July 2022 Alcaraz said: “Jannik, second time you beat me this year, I’m going to figure out how to beat you this year”. Which he did, in the epic 5 hour five setter in the US Open quarter final where he was just one point away from yet another defeat.

This year they are 1-1. Whereas most players are annihilated by the power and angles Alcaraz is able to generate, Sinner remains unfazed, and while hitting and counter hitting from the baseline, he succeeds in stretching the Spaniard to the end of the tether, on all surfaces.

As did Djokovic, in their only encounter, the famous and enthralling semifinal in Madrid last year. Alcaraz was at his top whereas Djokovic was nearing his best form. The score, 6-7 7-5 7-6, eloquently tells the story. Novak not only can erect an impenetrable wall, as Sinner, but can draw from an endless stock of tactical resources. He has also deftly employed dropshots in his past Roland Garros campaigns and can challenge Alcaraz in one of his favourite domains.

Zverev stunned Alcaraz in the quarterfinals of Roland Garros last year by dominating him long through the match. He constructed his victory with a high percentage of first serves, 73%, which allowed him to snatch control of the rallies. He was able to restrain unforced errors and land hefty, spinning and deep groundstrokes off both sides which forced Alcaraz to back away and muffled his penetration.

This year Zverev is still seeking such to recover such heights, but his achievement can be taken by others as a model to imitate.

The battle Jan Lennard Struff put up in the Madrid final a few weeks ago shows that players who are able to serve proficiently and return aggressively, finishing off rallies in few strokes, not letting Alcaraz make a first move, stand their chance.

That’s how Fabian Maroszan rose to fame. Alcaraz may have been in energy saving mode that day, but the Hungarian earned his glory by constantly aiming to dictate, scything forehands while standing right on the baseline and landing dropshots, giving Carlos a taste of his own medicine.

It is also interesting to recall how Emil Ruusuvuori won the first set against Alcaraz in the round of 32 in Madrid by hitting through returns with crisp anticipation, landing them on the baseline and continuously catching Alcaraz off guard. Another tactic to be taken into account.

A fascinating coincidence is that Alcaraz’s side of the draw is crammed with players who have inflicted defeat on him in the past. In order of potential clashes he could face in the third round Lorenzo Musetti, who beat him in the 2022 Hamburg final playing with an intensity he has not so often been able to maintain over a whole match. The quarter final could present him with Felix Auger-Aliassime or Sebastien Korda. The American surprisingly beat him at his debut on clay in Montecarlo last year, but Alcaraz shortly took revenge, brushing him aside in Paris at the third round.

Aliassime beat Alcaraz on two occasions in the 2022 fall season. First in the Davis Cup group phase in Valencia, one week after the Spaniard’s triumph at the US Open, then at the Swiss Indoor in Basel.

In his press conference on Sunday, Juan Carlos Ferrero said that Alcaraz is a better player this year, perhaps hinting that his protegee is not likely to incur such setbacks anymore.

And indeed history does not generally bother the young, it’s them, who are making it.