DIACHRONIC ANALYSIS OF THE BEST-PERFORMING FIVE COUNTRIES

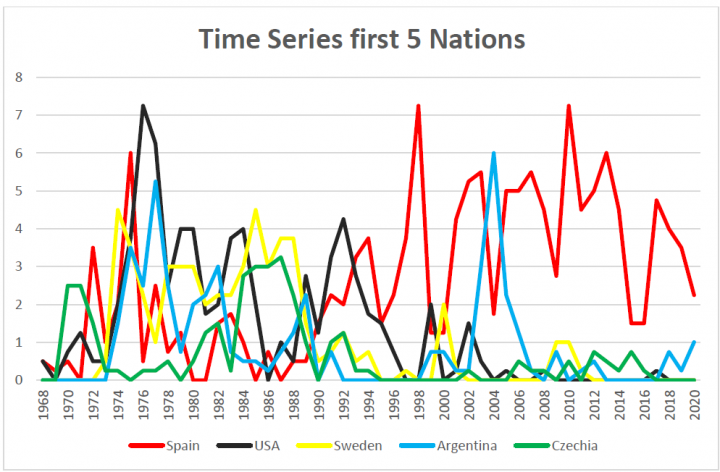

Let’s now look at the top five countries, namely Spain, the USA, Sweden, Argentina, and Czechia, focusing on their performance peaks.

It is worth mentioning the American peak of 1976 with a total of 7.25 points, 4 of them coming from Connors, 1.75 from Solomon, 1.25 from Dibbs, 0.25 from Stockton, and another one the next year peak with 6.25 points, 1.5 from Connors, 0.75 from Solomon, 1 from the late Gerulaitis, 0.75 from Dibbs, 2 from Gottfried and 0.25 from Stockton.

In the mid-‘70s, however, there were two different seasons on clay, one in Europe and one on North America, so that there were a maximum of 20 points available in 1975, almost twice as much as the current availability of 11 points.

The latest peak achieved by Americans was in 1992 with 4.25 points, while the total number of “empty” years is 19, which places in third place behind Spain and France in terms of fewest scoreless seasons.

As for Argentina’s performance peaks, they were achieved in 1977, a 5.25 soliloquy by Vilas, and in 2004 with 6 points obtained by Gaudio (2), Coria (2.5), Nalbadian (1), Chela (0.25) and Zabaleta (0.25).

It should be noted also that at the Hamburg tournament in 2003 the players from Argentina were able to monopolise the tournament by sweeping all the semi-finals spot, something never witnessed again in a Masters 1000 event played on clay.

Sweden and the Czech Republic dominated the clay seasons of the Eighties, bringing to mind a rendition of the battle of Prague in 1648, a battle never completely won by the Swedes, with the Czech leader Ivan Lendl playing the role of Rudolf von Colloredo, a warrior able to fight back every single time against the Swedish siege. The pinnacle of Swedish grandeur was reached in 1975 with 4.5 points scored by an illustrious Viking named Bjorn and in 1984, when Wilander with 3 points, Sundstrom with 1 point, Edberg and Nystrom with 0.25 points each contributed to the national now bygone pre-eminence. Indeed, the Viking wave – sporting the three crowns flag – retreated after Soderling’s final runs in 2009 and 2010, “the “invincible armada” returned to take over.

In fact, even if we remove Nadal, the man who single-handedly rewrote the history of clay tennis, Spain would still lead the combined rankings anyway, leading the US by 12 points.

The latest Spanish zero in a season on clay happened in 1987, with Spanish tennis players never falling below the 1.25 points achieved in the 1999 and 2000 seasons.

Therefore, the peaks of Spain in the 1998 and 2010 seasons are noteworthy, with 7.25 points out of 11 available, but also in 1975 with 6 points out of 22.

In 2010 Nadal scored 5 points, exactly like in 1975 when Orantes racked up 5.5, while in 1998 there was no standout player, and the point-grabbing appear more diverse. In that season Carlos Moya brought 3 points, Albert Costa and Alex Corretja both took 1.5, while Felix Mantilla had 0.75 and Alberto Berasategui 0.5.

However, at a closer look, since the beginning of the Nadal era Spain has never dropped below the 1.5 points mark from 2015 and 2016, years where the performance of the Manacor juggernaut was plagued by injuries, while many peaks where achieved in previous and ensuing years.

WAITING FOR ALCARAZ: A COMPARISON BETWEEN SPANISH GENERATIONS

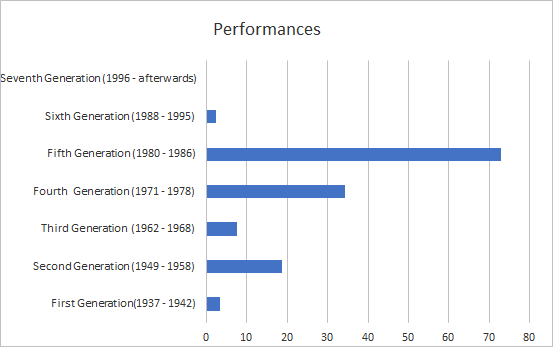

All of this forces us to start an evaluation on the performance of the different Spanish generations, while trying to discount the aforementioned Nadal effect.

The aggregate performances of the generations of Spanish tennis players was calculated, obtaining 7 generations, as per the following, with birthyears in brackets:

| First generation (1937-1942) | Second Generation (1949-1958) | Third generation (1962-1968) | Fourth Generation (1971-1978) | Fifth Generation (1980-1986) | Sixth generation (1988-1995) | Seventh generation (1996 onwards) |

| Manuel Santana | Manuel Orantes | Emilio Sanchez | Carlos Moyà | Rafael Nadal | Roberto Bautista Agut | Alejandro Davidovich Fokina |

| Andrés Gimeno | José Higueras | Juan Aguilera | Sergi Bruguera | Juan Carlos Ferrero | Pablo Carreno Busta | Carlos Alcaraz Garfia |

| Juan Gisbert | Fernando Luna | Carlos Costa | Alex Corretja | David Ferrer | Albert Ramos Vinolas | Bernabé Zapata |

| Francisco Clavet | Albert Costa | Tommy Robredo | Jaume Munar | |||

| Jordi Arrese | Alberto Berasategui | Fernando Verdasco | Pedro Martinez | |||

| Javier Sanchez | Felix Mantilla | Nicolàs Almagro | Nicola Kuhn | |||

| Sergio Casal | Albert Portas | Pablo Andujar | Javier Barranco | |||

| Tomàs Carbonell | Galo Blanco | Feliciano Lopez | ||||

| Roberto Carretero |

Below the performances by each generation

| Generations | Performances |

| First Generation | 3,25 |

| Second Generation | 18,75 |

| Third Generation | 7,5 |

| Fourth Generation | 34,25 |

| Fifth Generation | 73 |

| Sixth Generation | 2,25 |

| Seventh Generation | 0 |

It can be seen that, by removing Nadal’s points from the fifth generation, Ferrero, Ferrer, Robredo, Verdasco, Almagro and Andujar would have achieved 17.25 points, which is a very similar performance to that of the second generation, but the former achievement was spread between many more players.

The graph below summarizes these results.

The best Spanish generation in the opinion of the writer was the fourth generation, which expressed 9 players, even without an all-out legend:

CONCLUSION

At the end of this analysis based entirely on numbers, we think is fair to ask ourselves the following question: is it better to have an all-conquering champion with some young guns around him or to have many good players, an even-turfed lawn with a few flowers?

While the media are always in search of a mythical figure to write epics about, a setup that humans tend to be inclined to, the writer is partial to the even lawn concept, because it allows for a whole scene of different players to be at the forefront, as long as the results are consistent and fairly measured. Article and graphics by Andrea Canella; translation by Michele Brusadelli; editing by Tommaso Villa