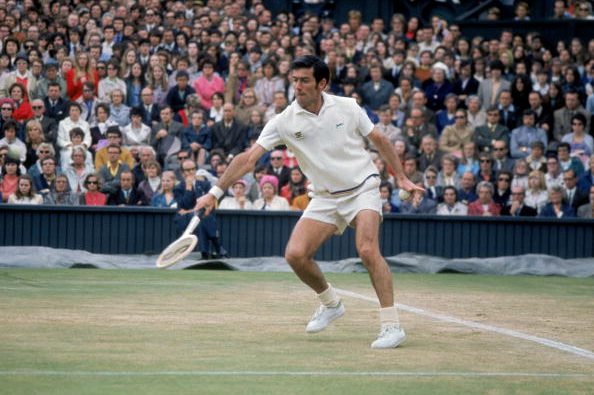

A kid sifting through tennis records from the 1950s to the 1980s might wonder – was that Rosewall always the same person or was it two brothers like the McEnroes? The most astonishing thing is not the sheer length of Rosewall’s career – the first and last of the Wimbledon finals played by the Little Master (5ft7 tall and 6.5 shoe size) were 20 years apart – but rather the quality of his tennis, which, on days of top form, allowed him to beat anyone, even at 40 years old. This longevity was a result of the technical elegance of his shots. That minute body of his was never under stress. When he was 53, he confessed sulkily: “I think I will have to have shoulder surgery – my first injury.” Nowadays, tennis players are all patched up at 25. Of course, his weak serve does not resemble the 140-mile/hour “cannonball” serves that we see these days. However, thanks to the wooden racquets and that surgical backhand of his, always hitting the most uncomfortable and remote spots, in the mid-70s Rosewall would easily return serves travelling at 125 miles/hour. Yet another secret for such a long-lasting career was possibly Wilma, his very loyal wife, whom he met when he was 14. She followed him everywhere with their two kids. Just like Mirka with Roger Federer – despite two sets of twins, she has always been behind him. Without great domestic harmony, it would have been impossible for Ken Rosewall to play for 30 years and win 8 Grand Slam singles titles. Absolutely amazing.

In the past half century, I bumped into Ken Rosewall several times – a champion who never acted like a diva. Yet, he was an idol for millions of Australians who knew that, in Rod Laver’s early years as a pro, it was almost always Rosewall who prevailed in their head-to-heads. Rosewall, however, like Laver, has always been a low-profile, sober man. A simple man, humble, accommodating and well-mannered.

He granted me his last real interview – which by the way was extremely lucid for someone of well above 80 years old – a couple of years ago at Wimbledon. However, the last time I talked to him was last year, on the morning of the Australian Open final won by Djokovic against Nadal.

As honorary secretary of the Italian International Club, I had been invited to the traditional lunch organised, like every year, by the Australian International Club. There were about a hundred people between members, relatives, former players and Australian champions. The lunch – with everyone in assigned seats – was held at the South Yarra Tennis Club in Melbourne, the superb and very refined club where the Australian legend Norman Brookes, a 3-time Grand Slam champion between 1907 and 1914, was born and raised – the first non-British tennis player to win a Wimbledon title. Some fabulous vintage pictures of Brookes dominate several rooms of the huge club house.

The seats were assigned in alphabetical order in a list that was displayed on a big board. As my surname is Scanagatta, by coincidence I spotted it in between Rosewall and Sedgman. Think about that, sitting in between two men who won 13 Grand Slam titles altogether because of my surname.

After lunch, we took a customary picture together – the two of them were very friendly and happy to recall funny anecdotes about Pietrangeli, Merlo, Sirola, Tacchini and others. I remember that Rosewall always used to say about Pietrangeli, “he had so much natural talent that, if we had all been stuck for months on a desert island without tennis courts and afterwards we had played a tournament without any training, Nicola certainly would have won it.” He said it again at the South Yarra Tennis Club that day and, while Sedgman nodded, I replied, “you may be right, but Pietrangeli’s opponent in that final would have surely been Ken Rosewall.”

Then Rosewall went on telling me a curious story that helps understand how things changed in the time between 70 and 50 years ago, let alone nowadays when whoever wins a Grand Slam title gets £3 million.

In the mid-50s, after he had lost his first Wimbledon final against Jaroslav Drobny in 1954, Ken used to sell his racquets as a side hustle. They had an image of him printed on the racquet’s throat, between the shaft and the head – they were called “Rosewall Slazenger”. He used to sell them to the ballboys, who were almost always children of members of the clubs that organised tournaments – they were so happy and always vied to get one. I wish Roche and Newcombe had sold one to me when I was a ball boy during their matches at the Florence Tennis Club. Although Rosewall’s racquets cost $35 on the market, he was selling them for $5. When Ken won the WCT Finals in Dallas in 1971 and 1972 beating Laver in two memorable matches, the first prize was $50,000. “Yeah – Rosewall recalled smiling – it took me 5 years but the jump from $5 to $50,000 was certainly a big one.”

As a comparison, in the early 70s, the US Open first prize – the tournament with the highest prize money – was $15,000.

Surely, Rosewall did not start playing for money. In his first tournaments, he would have been just happy with a cuppa. Ken never used to sing, dance, make jokes, or be noisy like Newcombe or Emerson. I think he possibly represents the most stereotypical example of Australian tennis player in those years – so painstakingly serious that he even used to stay away from the dark rooms of movie theatres as he was afraid he could potentially damage his visual reflexes. Yet, he was not a serve & volley player like the majority of the other “kangaroos” with a racquet. A racquet that he often let drop, demoralised by an error that only he would consider silly. When that happened, he would shake his head with a resigned demeanour, but never letting out a shout, let alone a swear word. No one ever heard him utter one. He would never want to make a mistake, give away a point, but he would also never steal a point that he didn’t win. The Little Master was also a big master of sportsmanship.

Translation by Tommaso Villa and Riccardo Superbo