There can be no indifference to what happened in America after George Floyd was brutally murdered by a policeman who had previously gotten away with multiple instances of violent, inhuman, and racist behaviour. “I can’t breathe” has become the motto of more or less peaceful protesters around the world.

What happened in Minneapolis stirred the public discourse globally, not just in the United States. Everybody knows that racism still exists, even if not as virulently as it did in the time of slavery. It’s not just an issue pertaining Trump’s America or its violent and aggressive cops, and it’s not just an issue pertaining football fans who taunt the other team’s black players.

A tennis website is not the most suited space for a discussion of the complex implications of racism – there are far more appropriate places and commentators than those that UbiTennis can offer. For the time being, all I want to do here is to say that there is no more dishonourable stance than to claim that the problem doesn’t exist, or that it’s being allotted too much room by the media.

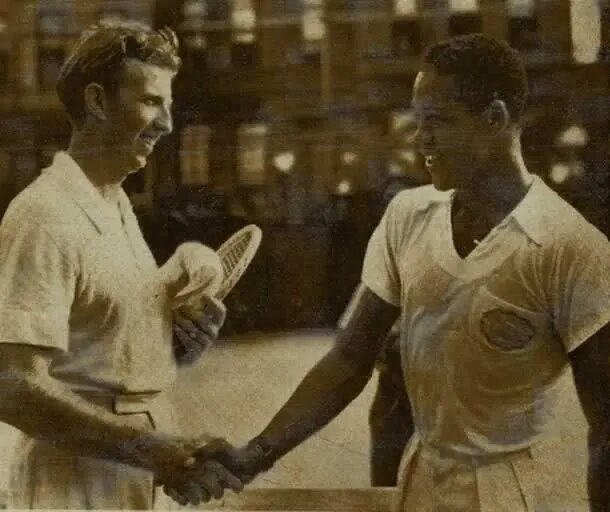

The problem exists, and we can all see it. Having said this, I’d like to do my part by reminiscing on the tribulations that so many African American tennis players have had to endure. The first example that comes to mind is that of Jimmie McDaniel, the best black player before World War II, a 6-foot-5 lefty who won the American Tennis Association’s segregated tennis championship four times, and who was “allowed” to play an exhibition match against Don Budge, the first man to complete the Grand Slam, on July 29, 1940. He lost that match, 6-1 6-2, but the encounter moved the American public, an extraordinary feat, especially given Jimmie’s turbulent past – the son of a Negro League baseball players, he had gotten a 15-year-old pregnant when he was 18 and had spent two years in juvie. Former Olympic medallist Ralph Metcalfe (he won four in Berlin, including the 4×100 relay with Jesse Owens, right under Hitler’s furious gaze, and had personal bests of 10.3 and of 20.6 seconds in the 100 and 200 metres, respectively) awarded him a track scholarship to attend the Xavier University in New Orleans, but Jimmie’s real penchant was for the racquet.

Another name is that of Oscar Johnson, from Long Beach in California, the first African American to win a national championship, the National Parks Junior Singles, when he was 17, in 1948. He died last March, after being awarded in Newport’s Hall of Fame in 1987, an accolade he received long before he was enshrined into the Black Hall of Fame in 2010. One more is that of Robert Ryland, one of the first two black players to compete in the NCAA tennis tournament, in 1946, who once recalled: “In those days, we had to face so many struggles due to racial discrimination. When we set out to go to play in Indiana, against Purdue or others, we used to send our white teammates to a restaurant, where they were allowed to sit and eat inside, so that they would buy us some sandwiches to have in our cars.”

In the ensuing decades, Althea Gibson rose to prominence after enduring all sorts of abuse, as did Arthur Ashe, who won the US Open in 1968 at Forest Hills, inside whose West Side Tennis Club he theoretically wasn’t have even allowed to enter, seven years before becoming the first African-American to win at Wimbledon. In 1981, Ashe said: “You can’t really compare tennis with football or basketball. When Jackie Robinson broke the colour line in ‘47 by starting for the Brooklyn Dodgers, there were dozens of good players in the Negro leagues who were ready to follow suit. When Althea Gibson, the first important African American woman in tennis history, won the National Championships on the grass of Forest Hills in ‘57 and in ’58, there were no talented black players waiting in line to cross that threshold. Black people don’t identify themselves with this sport, neither on nor off the court.”

In 1987, he added: “What we need is an American Yannick Noah. In many ways, I wasn’t a great model to follow. We need someone with flair and who plays a creative brand of tennis. And this person should behave like Julius Erving [Editor’s note: an NBA player, nicknamed “Dr. J”, who was famous for his athleticism as well as for his distinguished manners]”

Zina Garrison and Lori McNeil, who grew up playing on public courts in Texas, have told many stories about the abuse they had to face. Right now, I don’t have the time to fetch their autobiographies from my personal library to recount some of these unbelievable anecdotes, but I can tell you how embarrassing they are for any human being provided with even a shred of awareness and sensitivity.

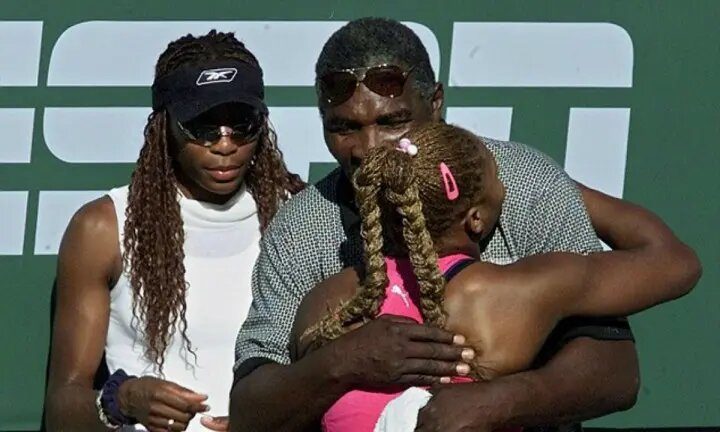

The Williams sister didn’t have it easy either. Although breaking out as champions when they were teenagers certainly opened a few more doors, their father, Richard Williams, never trusted this sort of indulgence. Maybe he exaggerated (but this is the type of character he was) when he said that the crowd’s racist taunts during Serena’s 2001 Indian Wells final was “the worst act of racial prejudice since Martin Luther King’s murder,” but it’s true that the crowd was utterly disgraceful that day, insulting him and Venus as well as soon as they took their seats in the stands.

I hope you will now forgive me for going through a collection of quotes on the subject, most of them by Ashe, a great man before he became a champion – the American delegate to the UN once said of him: “Arthur Ashe took the burden of race and wore it like a mantle of dignity” – and by a young Cameroonian, Yannick Noah, who was discovered by Arthur himself during a trip to Africa.

Here’s one of his memorable quotes then, pronounced in 1988: “Thanks to the combination of a few factors, black Americans now constitute the majority of athletes in all major sports. This didn’t happen in tennis because the sport was organised to discourage the participation of black people.”

I remember a fan in Rome cheering him on, “Daje Arturooo!” (“Come on, Arthuuur!”), during an indoor match, but I also remember the ineffable Ilie Nastase giving him the moniker of “Negroni” without pissing him off, at least until their match at the 1975 Stockholm Masters, when, under my own eyes, Ilie started to shamelessly complain about the lighting inside the Kungliga Halle: “Every time Ashe comes to the net I can’t see him, it’s too dark in here!” He said that, and more, until the match was suspended. Ashe, incensed like I’d never seen him before, walked out of the court, and the match was at first defaulted to his opponent, before the decision was deservedly overturned – Nastase was noted for his offensive off-court humour, and what’s more baffling is that he used to say, “hi, racist!” every time he ran into South African players like Drysdale or McMillan.

I recall one of Arthur’s prophecies, from 1992: “It’s more likely that the next black Slam champion will be a woman rather than a man. The best male athletes still prefer basketball, football, or track.” It’s fair to say that the Williams, who were initially nicknamed “the Ghetto Sisters” by the press, fulfilled this forecast, and then some! Serena won 23 Slams to Venus’s 7…

Even before them, though, Zina and Lori gave us something to remember at Wimbledon, where the former reached the final and the latter upset Steffi Graf in the first round, whereas in the men’s field only MaliVai Washington broke through at SW19 by reaching the 1996 final after a comeback from 1-5 down in the semis against Todd Martin. Washington then lost to Krajicek, and once said: “It’s very hard for a black kid to identify with a white tennis player. I mean, who is he more likely to identify with, Michael Jordan and Walter Payton or Boris Becker and Ivan Lendl?”

In 2006, James Blake, the son of an African American dad and of an English mum, reached the highest ranking for a black player in the new millennium at N.4 – he is now the director of the Miami Open.

Althea Gibson once said: “In sports, you’re more or less accepted for what you do than for what you are.” She also added: “No, I don’t see myself as a representative for my people. I think about myself and nobody else…” Another time she was been asked whether she was proud of the Jackie Robinson comparisons that were thrown her way after winning Wimbledon in 1957, to which she replied: “I’m not aware from a racial standpoint… I’m a tennis player, not a Negro tennis player.”

On the other hand, Ashe once said: “I remember that there were some rules meant for Southern black kids. When you were unsure about whether a ball was in or out, and you were playing against a white opponent, you had to call it in. [Editor’s note: I spent some time studying in Tulsa, in Oklahoma, and back then matches were self-regulated at the university level, so I remember my embarrassment for having to call some lightning serves on hardcourts, where the ball leaves no signs – I didn’t want to be thought of as a cheater, but at the same time I didn’t want to give away any points.] Another rule was: if you were serving before a changeover, at the end of the game you had to pick up each ball and give it to your opponent when you walked past him. Doctor Robert Walter Johnson, our coach [at UCLA, in Los Angeles], knew that we were going to a hostile place, so he wanted our behaviour to be irreprehensible. It would take me years to get over such an emotional toll of suppressed rage and frustration!”

One time, Ashe was a guest at my tournament in Florence, where I had also organised an exhibition for his delightful wife, who was a professional photographer, and he said: “Every day I close my eyes and pray that people won’t be as cruel to my children as they have been to me. What drives me mad is walking into someone from my hometown of Richmond, Virginia, only for them to say that they saw me play at Byrd Park when I was a kid. Well, no one could have seen me play there, because at the time Byrd Park was open only to white people!”

Yannick Noah, the last French to win at Roland Garros in 1983 (and the last French man to win a Slam altogether), was born in Sedan, Northern France, and talked about a different brand of racism early on in his career: “I never had any issues with being black, but the Cameroonian Federation could never stand me. The reason? My mother was white. I’m not an ambassador for any race or country precisely because of that: my mother being white and my father being black… inside I don’t feel neither white nor black. I think I did more for people by winning the French Open than I could have by going to South Africa to give speeches against apartheid. Maybe someday I’ll change my mind, perhaps when I’m 35, but I don’t think it will happen.”

However, when Noah changed his hairstyle to his signature dreadlocks, he noticed that white people in France had a harder time accepting him: “All of a sudden, I wasn’t a tennis player anymore. I was black and I was a nobody. People’s reactions became completely different. Nothing terrible, nothing that could lead to a physical fight, just different. And I’ve actually never had any issues being black here [in America]. It’s like Larry Holmes says: ‘if you’re black and you have money, then you’re not black.’”

Even this last quote has some counterarguments, though, because, as Felix Auger-Aliassime said, “if you are driving a Mercedes, cops tend to stop you, like they did with my father, because they think that you probably stole it.”

Katrina Adams, a former player who reached the 67th spot in the WTA Rankings and a doubles semi-finalist at Wimbledon in 1988 (partnering Zina Garrison, has become the first African American USTA president, and also the very first to get a second term, thanks to the withdrawal is a individual set to replace her. If things do not change racism-wise during her tenure, at least in tennis, they’ll probably never change.

Translated by Tommaso Villa