One of this year’s major US Open stories is in the numbers. The tournament is the fiftieth of the Open Era and the fortieth time it has been staged at the Billie Jean King National Tennis Center. But, for a select group of tennis devotees the August 27th until September 9th event is even more significant. It offers a “Lookback” opportunity, in truth a celebration, of Joe Hunt’s championship victory seventy-five years ago.

In 1942, Ted Schroeder slipped past Frank Parker in the US National Championships singles final, 8-6, 7-5, 3-6, 4-6, 6-2. A year later, Schroeder, in the military because of national preparation for World War II, was unable to defend his title. Joe Hunt took full advantage of the situation. In another All-American contest, on a brutally hot and humid afternoon, he defeated Jack Kramer for the title 6-3, 6-8, 10-8, 6-0 on the grass at the West Side Tennis Club in Forest Hills, New York.

When Kramer’s last shot traveled long, Hunt collapsed on the baseline and simply sat there, because he had leg cramps. His opponent, who had his own issues dealing with food poisoning during the tournament, was similarly exhausted. He, none-the-less, hopped the net then sat down next to the winner, and shook hands with him. Many years later, Kramer jokingly commented that although he was weak, if he had been able to last a bit longer he may have triumphed by default.

Seventy-five years ago, the world was different. Beginning in 1939, World War II had devoured borders and changed Europe and Asia, (and not for the better). There were food and production shortages, and lifestyles were frequently altered. From a tennis standpoint, the annual fortnight in New York became a six-day tournament. The singles draws featured 32 players while the doubles had 16 tandems. Since many of the men were involved in military service, those participating in the event were not “match fit”. They hadn’t been competing since it was next to impossible to get leave from military commitments and, coupled with travel and gasoline restrictions, players were not focused on playing tennis tournaments. In fact, the US National Championships, (the only one of the four majors to be held during the war), had to rely on the government to release “limited amounts” of reclaimed rubber so that tennis balls could be made.

(Hunt would subsequently die fifteen days shy of his 26th birthday on February 2, 1945 when his Navy Hellcat, a WWII combat aircraft, crashed into the ocean while he was on a training flight off the coast of Daytona Beach, Florida.)

Hunt’s great-nephew, Joseph (Joe) T. Hunt grew up playing tennis in Santa Barbara, California. He is now an attorney practicing in Seattle, Washington and he takes advantage of opportunities to get on the court regularly. More important, he has led the family’s effort to ensure that Joe Hunt isn’t forgotten.

“I have to really spend some time to gather my thoughts on what the Seventy-fifth Anniversary of Joe’s victory means,” he said. “I have so many of them. Joe was a patriot from what is considered the greatest generation of our nation. He is the only American tennis champion to lose his life serving his country in a time of war. We lost him so early and so young. He never had a chance to reach his full potential, yet he accomplished so much by the age of 25. He was a remarkable young man, devoted to tennis, devoted to his family and devoted to his country. The family lost him, and tennis lost him. Over time, while the family continued to grieve the loss of our uncle, brother and son, tennis seemed to forget and not consider the meaning of this loss to the game.”

Tennis historians credit Kramer for developing the “Big Game” – meaning being a serve and volleyer. According to Bobby Riggs, a contemporary of his, Hunt used the tactic before the iconic Kramer.

“As maybe the first true serve and volleyer, Joe was changing the game itself,” his great nephew said. “He never had a chance to tell his story from his perspective. I feel I have been his only voice in trying to tell the tennis world who he really was and what we all lost.”

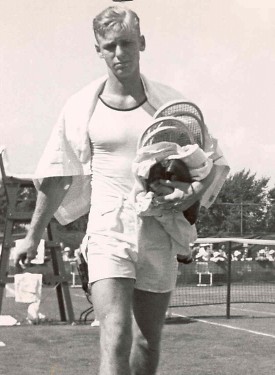

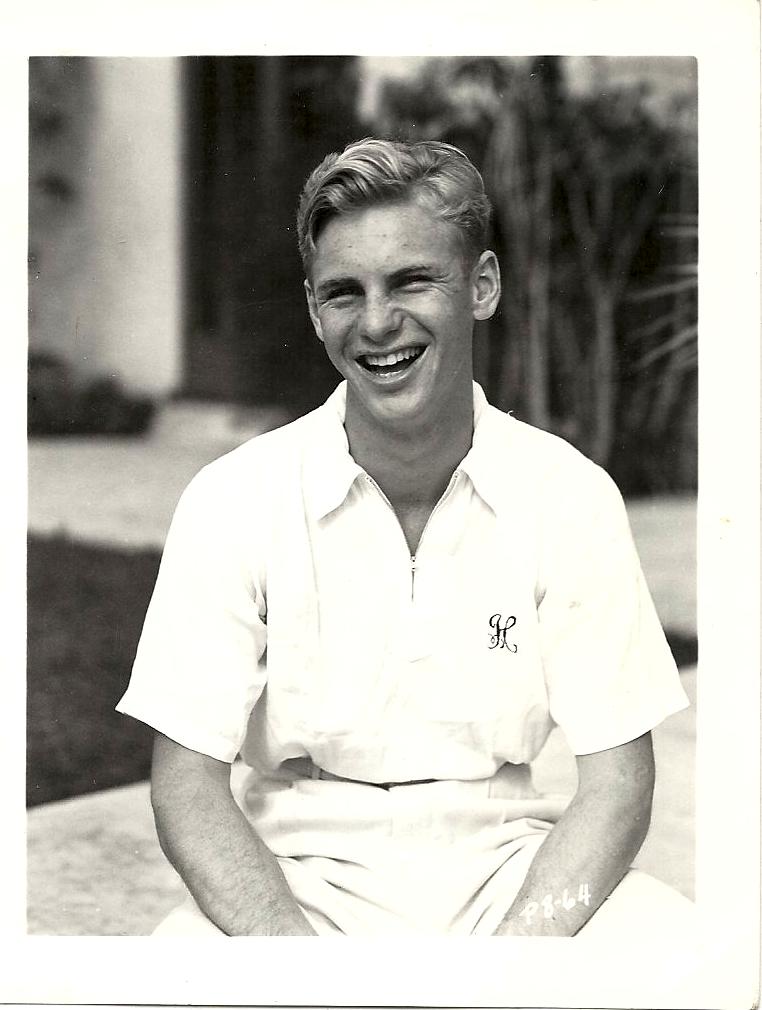

The original Joe Hunt was one-of-a-kind not only because of his athletic ability, but also because of his blond good looks and his marvelous charisma. As a junior, he was a star, winning the National Boys’ 15 and 18 titles. By the age of 17, his success on court earned him a US Top 10 ranking. In 1938, he was USC’s top player and didn’t lose a singles or doubles match. He enlisted and transferred to the US Naval Academy. In 1940, he was a halfback (American football) and played against Army that season, earning a game ball for his outstanding performance. The next year, he became the only competitor [ever] from the Naval Academy to win the NCAA singles championship.

Hunt continued, “Joe went out for football at the Naval Academy because he loved that sport too. He also wanted to be part of a team. He was the most famous player on the football team by a mile, and it wasn’t for football.” But, with all his stardom, he spent the hot summer and chilly fall getting pushed into the mud by seasoned players who wanted to make sure he knew he was no ‘star’ on their field. And he was fine with that. When he had the choice of skipping football practice so that he could play Forest Hills and possibly win it, he went to football practice. He would not let his teammates down, even though he was destined to spend more time on the bench than on the field as a backup running back. But, those on the football team respected him for it. They knew Joe’s tennis hands and legs were Davis Cup commodities and they saw Joe give them up for the team they were on. That is why they gave him the game ball for the 1941 Army Navy game, and every teammate signed it for him.

“Now, after seventy-five years, the last remnants of the greatest generation are bidding farewell, and we as a nation are at a moment of moral truth. How are we to say goodbye to them? How are we to remember and honor them? How are we to protect their legacy of saving the world for future generations? Each soul lost in the war effort is a part of that legacy. How will tennis address this? We just saw a great remembrance of the return of the bodies of men who gave their lives in the Korean War. Bringing home, the bodies after so many years was hugely significant to the families and the nation. I think of Joe’s body, never recovered, at the bottom of the Atlantic with his plane. It’s a sadness our family still bears.”

The times were unparalleled, which makes it no surprise that an unmatched backstory resulted. “I know that Joe was not the only player to not have a chance to defend his title, because Ted (Schroeder) won it in 1942 and was not able to defend in 1943,” Hunt pointed out. “They both were Navy fliers stationed in Pensacola, Florida. Neither was granted leave to play Forest Hills so they both entered the local Pensacola tournament held at the same time as the National Championships. Of course, the local tennis community couldn’t believe their lucky stars to have the 1942 and the 1943 champions playing in the tournament. It was billed as the ‘Clash of Net Champions’ and would supposedly determine the true No. 1 player in the country, despite that ‘other’ tournament taking place in New York. Joe and Ted both reached the final where ‘urban legend’ has it that they played their match in front of thousands on September 4, 1944, while Frank Parker was playing Bill Talbert in the final of Forest Hills (and winning 6-4, 3-6, 6-3, 6-3). I have spent hours trying to vet the truth of this story. I know that it is true, I just don’t know if it is 100% true that the two finals were played simultaneously. In any event, Joe beat Ted 6-4, 6-4. Despite what many have written, this was, in fact, the last tournament match of Joe’s life.”

Seventy-five years was too long ago to remember for most of us. Memories and treasures from that time are scattered here and there. Some are lost forever. In the case of Joe Hunt, his accomplishments, along with the individual himself, should not be left covered in dust and diminished by the passage of time.

Great nephew Joe Hunt said, “I think of a young man who stood for literally everything that is true and good in sport. An amateur who wasn’t seeking to profit off his game. He left his immensely successful life in Southern California to enter the Naval Academy, knowing that it would literally make it near impossible to achieve his dreams as a tennis champion. He intrinsically understood sportsmanship, camaraderie and good will. Everyone loved Joe. He played for all he was worth, but never took a ‘win at all costs’ approach to tennis. He put the right things ahead of the game.”